Kids smart tracker watch security: everyone has missed the point. It’s not a few thousand here and there. It’s at least 47 million, probably around 150 million exposed tracking devices.

It all points back to two or three lazy device manufacturers, much like Mirai v1 did

There have been lots of smart tracker watch security stories. Probably the first was @skooooch who raised serious concerns at Kiwicon about 360,000 car trackers and engine immobilisers in 2015. Lachlan also flagged the connection to thinkrace and kids tracker watches.

Others all missed the point, including us:

- The Icelandic data protection authority banned Enox, missing the point

- AVAST missed the point, with about 230,000 watches

- Rapid 7 missed the point with the G36 and SmarTurtles watch

- AV-TEST missed the point with the SMA watch

- The Norwegian Consumer Council missed the point

- And yes, we also missed the point last year

And with ~47 Million devices exposed to compromise, one can do some really interesting things, including winning reality shows and other TV shows that rely on audience voting by telephone or SMS.

That’s in addition to retrieving or changing the real time GPS position of millions of kids, the ability to call and/or silently spy on them, or just discover audio recordings hosted in publicly available repositories:

The above image shows real-time tracking of a child (actually my own kid!) walking around London with a tracking watch on, without needing to authenticate to the correct API account.

Why did everyone miss the point? You just have to follow the breadcrumbs through the API:

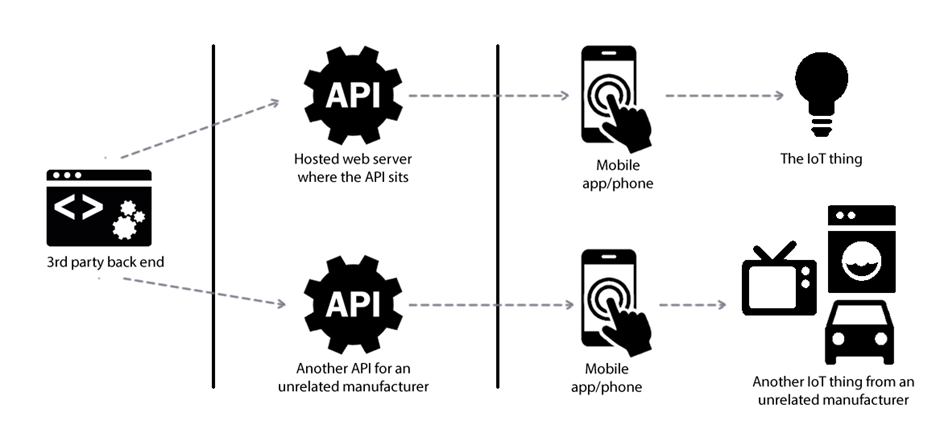

IoT Platforms

White labelling is rife in IoT, particularly with products manufactured by Original Device Manufacturers (ODMs) in the Far East.

IoT platforms are also increasingly common, as it cuts down the time-to-market for a start-up, if they can simply ‘bolt on’ an API and cloud platform from a 3rd party.

Combine the above and you have a recipe for disaster:

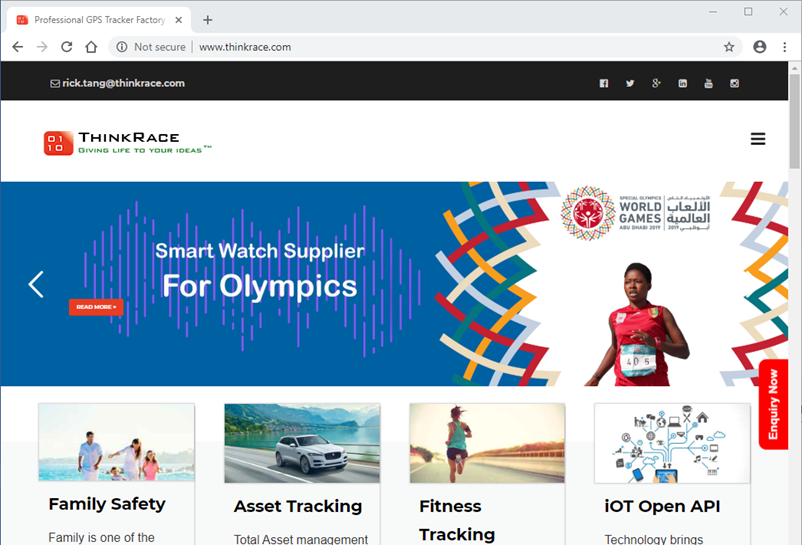

Example: thinkrace

One of the largest and worst tracker ODMs, in our opinion, is thinkrace. This Chinese watch and tracker manufacturer also provides an API and cloud platform to quickly deliver white labelled tracking devices and kids tracker watches to international market.

There is a complex ODM / distributor / importer / brand owner / white label operation which makes it very hard to determine a common point of failure…. unless you follow the API trail

Often the brand owner doesn’t even realise the devices they are selling are on a thinkrace platform.

The Icelandic Enox watch? A thinkrace API

The AVAST T8 watch research? A thinkrace API

The AV-TEST SMA watch research? A thinkrace API

Etc…

Back in 2015 Mich Gruhn @0x6d696368 and our Vangelis @evstykas found a ton of flaws in around 370 different device types affecting upwards of 20 million devices around the world. The majority of the issues discovered were simple failures to authorise requests correctly: IDORs (Insecure Direct Object References) aka BOLA (Broken Object Level Authorization).

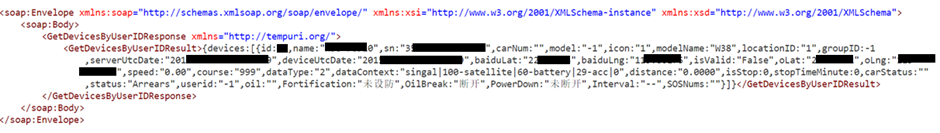

Put simply: the watch APIs were failing to check that the correct user was making the request to retrieve the kid’s data. This mean anyone could request any kid’s data

Their work showed some common points of failure, which we dug deeper in to this year.

Vulnerabilities

Putting aside the default creds and permissions issues that researchers keep finding on individual watches, thinkrace really are a monstrosity of fail.

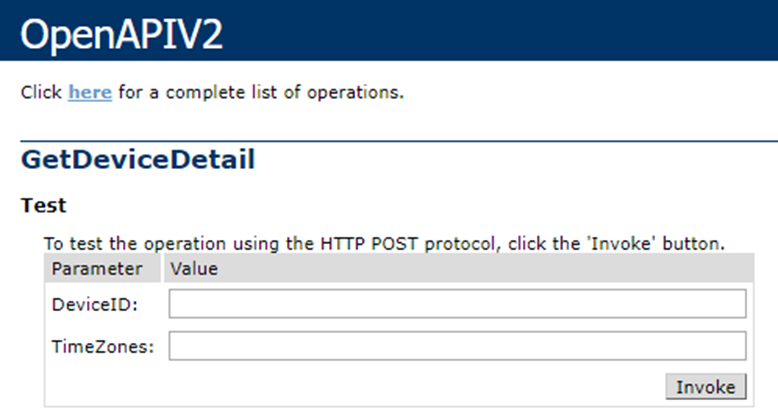

Most API calls don’t need authorisation, they are very well documented within the service itself – literally just browse to the Web Service Descriptions Language (WDSL) file.

All variables simply increment integers meaning you can brute force and also deduce numbers of devices with ease.

Add a new account, see the ID number, then add another new account and see the ID number increase by one.

In virtually all devices (including non-thinkrace) we have seen the default password is 123456!

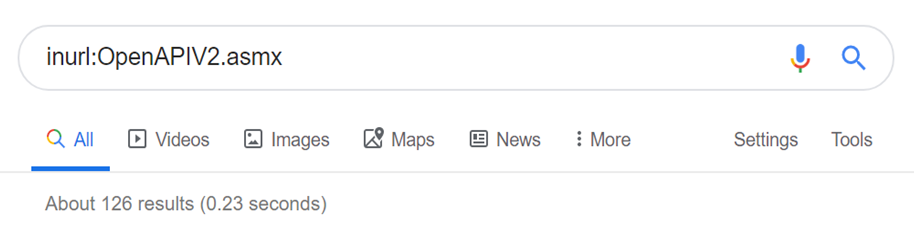

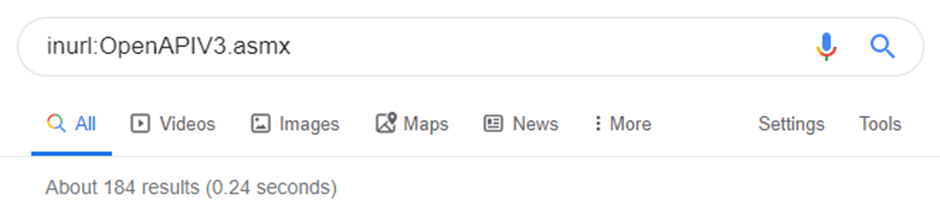

Identifying thinkrace devices

There’s a Google Dork for that! These will find you some of the devices:

Some of the trackers have a web app too. If yours looks like this, it’s probably thinkrace also:

Searching for devices is trivial, just enter your device ID in to the GetDeviceDetail API operator and receive all the detail on your device. Given the lack of authorisation, one could retrieve any child’s data if one wanted. 20 million kids and trackers.

You can determine the location of the device of course through the Lat / Long of the device, but also the country from the phone number of the device and the ‘family number’:

thinkrace exposed the safety of disabled athletes

They sponsored the Special Olympics / Paralympics World Games earlier this year. Every athlete was given a tracking watch, thereby exposing vulnerable adults to privacy and stalking attacks. We found this very distasteful indeed.

Look closely at the athlete’s wrist on their homepage. There’s the offending watch:

The scale of the problem

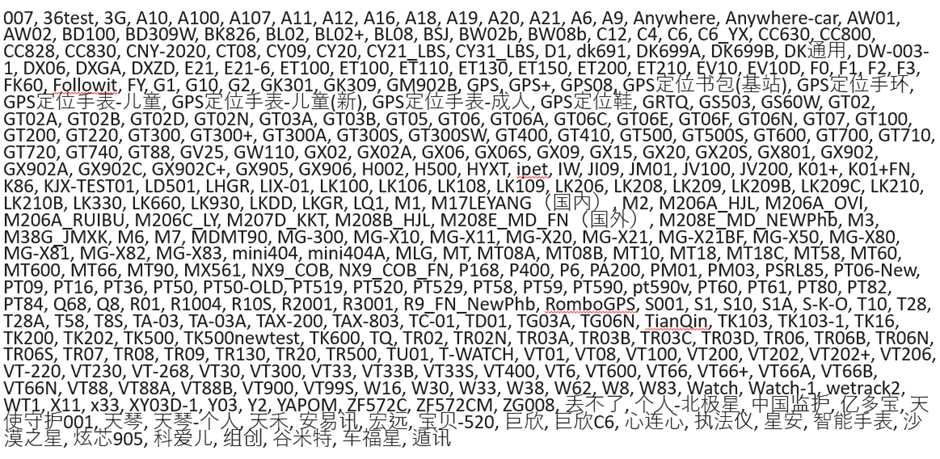

thinkrace produce 367 different types of tracking watch and tracker, making device identification and attribution to thinkrace very difficult, unless you follow the API. Here are a few – some include camera functionality.

Here’s a list of some offending device part numbers. Unfortunately these are often changed by the importer or brand owner, so this rarely helps identify vulnerable devices in your region:

But then we find that they don’t connect to one, common API. Instead, multiple endpoints across apparently unrelated domains are used, depending on the product and importer/distributor. Here are a few of the >80 we found.

Dig deeper and we find that they’re nearly ALL thinkrace API endpoints. In some cases, we think thinkrace code may have been sold or ‘appropriated’ by other manufacturers, but it’s still just as vulnerable. It appears the code was written in 2012, as indicated by the ‘newgps2012’ name for the portal code

5gcity: It’s CloudPets all over again

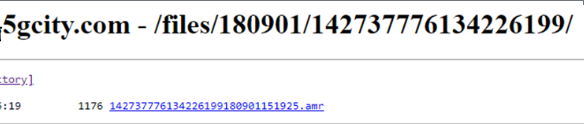

Last week, we were looking at 5gcity.com – another one of the tracker domains associated with a thinkrace API. It has around 5 million users, mostly kids tracker watches.

One of their web servers is exposing thousands of .amr files:

We believe these are audio message recordings of messages sent from child to parent using the watch and from parent to child.

5gcity has the same vulnerabilities as we would expect to find in a thinkrace API:

Reset any users password and hijack account

Full access to source code

Full user enumeration, leading PII of kids and parents

Send commands to any device, reflash the firmware remotely

Track any device

…but the audio file leakage was a new one for us!

A few more thinkrace API devices

www.goicar.net – around 3 million active tracking devices

www.gps958.net – around a million devices active

And one that isn’t thinkrace

www.gpsui.net – around a million active devices

Each domain we enumerate devices on contains millions of tracking devices. So far, just looking at thinkrace we’ve hit over 20 million devices. Digging further, we’ve found another 27 million devices on other ODM APIs. We think we’ve only seen the tip of the iceberg though

Another Example: Gator / Caref Watch Company

We’ve covered this security train wreck of a firm in the past: it’s not that dissimilar to thinkrace, but on a much smaller scale.

Again, the complex ODM / distributor relationship makes identification of Gator watches harder. In one case, the Australian importer rebrands the watch as TicTocTrack. In the UK it’s known as TechSixtyFour.

There’s also another ODM platform that we’re investigating right now, with ~100 million devices.

Disclosure

Mich & Vangelis disclosed the API flaws to the various ODMs back in 2015 and 2017. Various other researchers attempted to contact thinkrace over the years, to no avail.

Indeed, the Icelandic data protection authority banned some thinkrace watches sold under the Enox brand. How did thinkrace not change their ways then?

The German telecommunications regulator, Bundesnetzagentur, banned many kids smart watches in 2017.

Various watch brand security issues have since drip-fed in to the press, also with no response to responsible disclosure attempts. There is now evidence of these issues being exploited by criminals (see below), so we have to act.

Some of the other vendors involved in Mich & Vangelis’s work fixed issues in some of their API endpoints, but not all. We’ve since found that some of the vendors have actually UNFIXED their APIs since.

Exploiting this: winning Eurovision and The X-Factor

Every GPS tracker also has a SIM card in it. The tracker needs the SIM in order to communicate with the API over mobile data:

So how can we abuse the SIM?

With the flaws in the API, it’s possible to make the tracker watch dial phone numbers or (in some cases) send SMS messages.

Phone Voting

Phone voting in talent shows is a simple and effective way of abusing this. Many high profile shows use phone voting, e.g. Eurovision, X-Factor, Strictly Come Dancing etc and there is usually a short dial code for the act you want to win. Dial it once and your vote is counted.

Could votes be influenced and shows be won? Yes!

Could the UK win Eurovision through this? With a good song, watch SIM calling could be used to push the UK to the top of the ‘Televote’. To vote for the UK you would need to exploit SIMs in one of the other countries taking part. Bear in mind there’s a ‘Jury’ vote too, so maybe, just maybe.

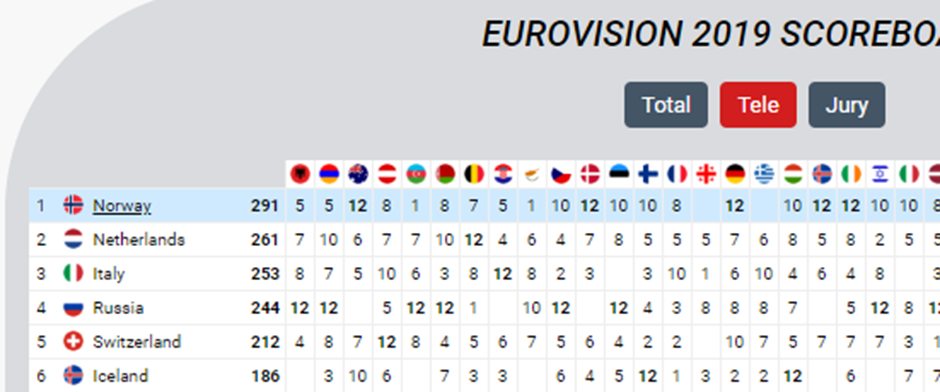

Here’s Norway at the top of the Televote:

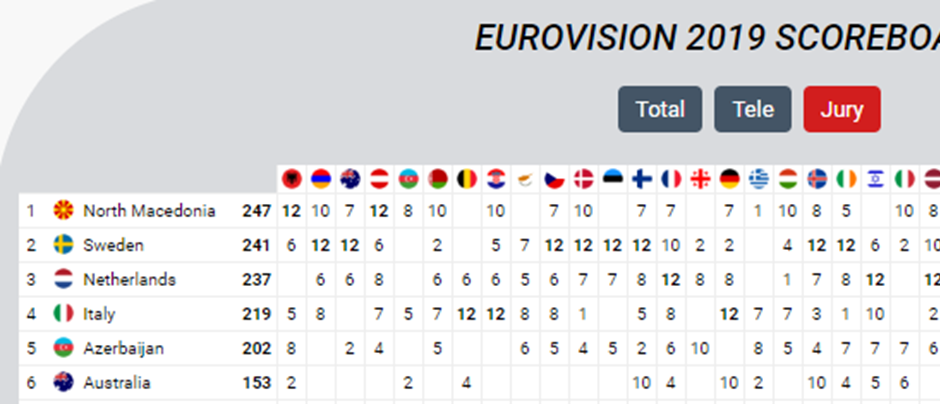

But only 18th in the Jury vote:

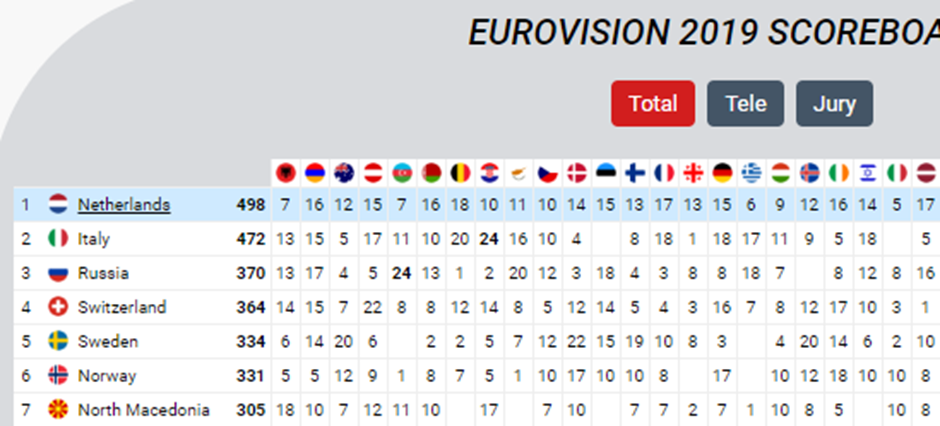

These combined together meant that the Netherlands came out on top.

Shows like X-Factor and the finals of Strictly Come Dancing that use 100% audience voting are much more easily manipulated:

Worked example

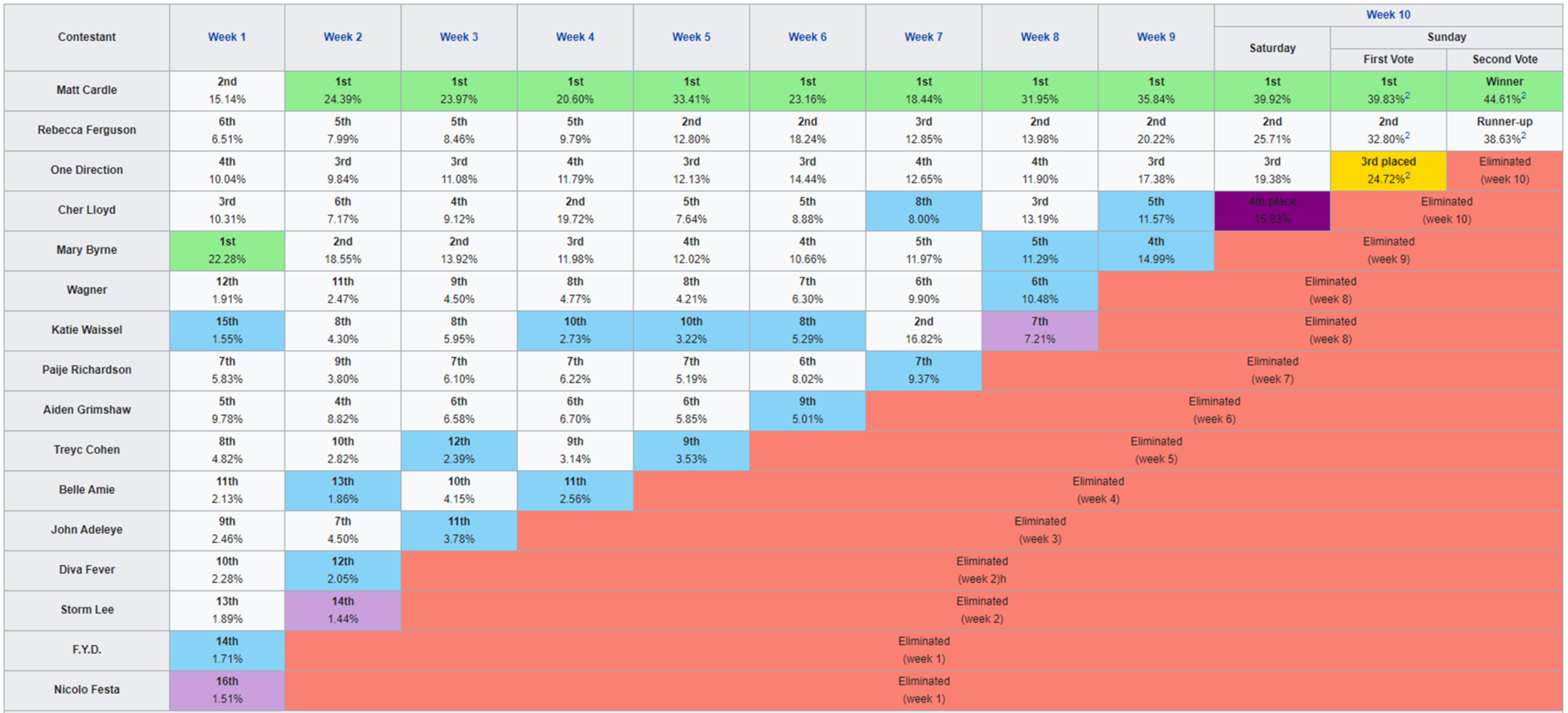

X-Factor UK 2018 was won by a 12% swing. Actual voter numbers were not released in 2018. However, in 2010 X-Factor confirmed how many votes they had across the whole series: this was just 15.5 million votes. The show was broadcast for 10 weeks, with each week having a vote, with three on the final week. Assuming an even spread that’s roughly 1.2m votes each week. The final in 2010 was won by just 6%.

This means to win the final just 72,000 votes would have been needed. Although it is expected that more votes would be recorded in the final.

We’ve found 47 million devices that could be triggered to make calls. Each is likely to be able to make ~10-20 premium rate calls before the credit is exhausted. That means up to a billion votes could be injected!

Default settings on phone services

On the 4 main UK providers, excluding MVNOs, ALL of them have premium lines enabled by default on non-contract SIM cards As long as you have credit you can be charged to vote.

We think it would be very wise for premium numbers to be blocked by default, significantly mitigating this attack. For users, we strongly advise you to block premium calls on your SIMs if you haven’t already.

Detecting voting attacks

That’s where this gets difficult: the voting attack is distributed across millions of phones. How would one determine which call was legitimate and which wasn’t?

Is anyone else exploiting this?

Voice Kids Russia was subject to suspicious voting patterns in May this year, as covered by the BBC. It is not clear exactly how this happened, but bots were suspected.

The attack was detected due to the attackers using consecutive numbers to make phone calls and sending thousands of SMS messages from one area. This ultimately led to the result being cancelled.

Simply spread the calls or SMS over millions of phones and there is no pattern to spot.

What can I do?

Stop using trackers: we have rarely found any kids watch, pet or car trackers that does not have vulnerabilities. Power the device off. If you identify your device is from thinkrace (harder than it sounds) it may be prudent to simply request a refund.

Conclusion

The tracking market is exploding; the race to market has meant that security corners have been cut.

This is a new attack which is not yet being widely exploited, though we have seen evidence on online forums that exploitation is happening.

Manufacturers need to get better at building secure systems. There is no excuse for poor security now, given the vast quantity of good advice already on the public internet.

Regulators need to get better at regulating against devices that expose our children’s data.

Enforcement action needs to be taken; ensuring that bans cover the entire white-labelled ecosystem, not just individual brands.